For a while now, I have considered that there is a problem with the English language teaching profession. And in this post, I would like to explore it. The post is divided into six short parts. (Note that this was originally shared as a LessonStream Post on Sunday November 8th 2020.)

1. The invisible plenary speaker

A few weeks ago, I took part in an online conference. It was very well organised and I attended some interesting talks. But there was something notable about the plenary session – not once did I ever see the presenter.

For 60 minutes, my computer screen was filled with text and images. The speaker (who spoke well, I should say) was always there to be heard but never to be seen.

It is very possible that there was some sort of technical problem. But even when speakers are visually present, they are usually relegated to an image the size of a postage stamp at the top right corner of the screen.

Anyway, this got me thinking – why do we allow power point to dominate ELT (English Language Teaching) presentations, whether they are delivered online or in physical space?

Having coached a number of teachers through their first conference presentations, the thing that has frustrated me most is fighting against the assumption that every single utterance that comes out of the speaker’s mouth must be accompanied by a power point slide.

2. Do you mind if I just step down?

Here is another observation – this one from the days when conferences took place in real space.

The conference speaker starts the talk on a stage. But very quickly, he or she makes a point of stepping down into the space below – immediately in front of the first row of teachers in the audience. And that is where they stay for the next hour or so.

I have even heard presenters justifying this action as they do it: “I hope you don’t mind if I just step down here. I don’t feel very comfortable about being the centre of attention.”

Doesn’t this seem a bit anti-communicative and odd? The audience expects a presenter to be the centre of attention. That is why stages were invented. And as soon as we step off, without good reason, we deny our audience the basic experience they expect.

3. A profession with a problem?

Of course conference speaking is not language teaching. But at an ELT conference, most presenters are – or will have been – English language teachers at some time. We all belong to the same profession. And the older I get, the more I feel that it is a profession with a problem: We feel awkward or uneasy about being at the centre of attention, even though it is something that our jobs fundamentally require.

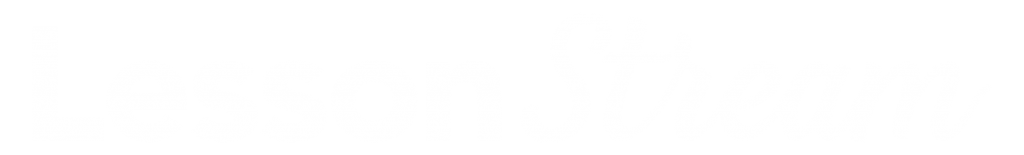

My own insecurities go back to the year 2000. I was doing a CertTESOL in Barcelona and for my third teaching practice session, I had to do a speaking activity. It went pretty well as far as I can remember – much better than the previous grammar lesson which was a complete disaster!

But then, 5 minutes from the end of the lesson, I had a moment of panic when I finished the planned activity just a little bit early. Realising that I had to improvise, I decided to tell my students a joke.

I’ll spare you from the details of the joke as it wasn’t particularly funny. But I will show you the feedback that I got from my tutor:

The message was clear: the teacher should not be the centre of attention in the classroom. Teacher talk is bad and should be avoided. Student talk is good and should be encouraged.

This made sense to me. I had just started to learn Spanish and was aware that I needed to exercise the parts of my brain and mouth necessary for communicating in this new language.

So I took the advice on board and looked for ways to get students talking.

4. Discovering Dogme

In an attempt to get students talking, the course book was an obvious starting place. After all, it seemed to provide everything that I needed and much more. But unfortunately, the course book that I was obliged to use just didn’t cut it. The stories were weak and my students’ engagement was low.

It was then that I discovered Dogme ELT. Dogme is a movement of English language teachers which, in part, came out of a reaction against course books. Proponents of Dogme encourage a greater focus on conversation and communication – “a pedagogy of bare essentials” as founders Scott Thornbury and Luke Meddings put it.

[Note: if you are new to Dogme, this article provides a pretty good summary of what it is: What is Dogme ELT?]

All these years later, I am still unclear as to whether there was a misunderstanding on my part. As I understood things, it was important that conversation and discussion should originate from the students. It was the teacher’s role to manage the discussion as a conductor would manage an orchestra – preferably in silence! From out of that discussion, language would emerge and teaching opportunities would arise.

5. Getting students to talk

It all sounded great. But how do you get your students to talk? How do you initiate discussion without dictating the agenda? I spent a huge amount of time trying to find ways to make this happen.

With my CertTESOL training still fresh in mind, I recalled the incredible praise that one of my peers had received upon managing to conduct an entire 30 minute-teaching practice session in total silence through the use of mime.

There’s no way I was going to try that. But I did have another idea. Perhaps image provided the key? I started to experiment with ways to use images to get students talking.

And then, one day, I had one of those personal experiences that informs us about our practice – a memorable incident that would seem to validate, or otherwise, our classroom approach.

Here is how I remember it:

I was teaching English to a group of lawyers in Barcelona. One afternoon, I was sitting at the front of our meeting room where our classes took place. I had connected my computer to a TV and had already greeted my students who were sitting patiently around a large table in the centre of the room. And now, I was slowing moving through a slideshow of carefully-prepared images which were displayed on the TV screen behind me.

With little or no teacher input, I was hoping that sooner or later, one of the images would grab the attention of a student and get him or her to talk. If I was lucky, this would provide the necessary spark for a class discussion.

But no one was taking the bait. And for a few minutes, all I got back was some very confused faces – perplexed, you might say.

Then one of the senior members of the company sat up, leaned forward and said:

“Jamie! ¿Qué coño haces? ¿Qué quieres que hagamos? Cuando vas a empezar a enseñarnos?

[Translation: Jamie! What the hell are you doing? What do you want us to do? When are you going to start teaching us?]

6. Suppressed voices

With hindsight, this experimental approach may seem laughable. But we are part of a profession in which teachers are trained to be technicians or silent ghosts who hide behind machines. At worst, our jobs would seem to be reduced to that of button pusher or instructions giver.

“Open your books at page 48 and let the lesson begin.”

And if you think that that sounds strange, let me remind you that in 2014, a man called Sugata Mitra gave a plenary at the annual IATEFL conference in Harrogate – the largest conference for English language teachers in Europe. Perhaps you remember him as the man behind the Hole in the Wall project.

The Hole in the Wall project involved Mitra installing a computer terminal in a wall in a New Delhi slum and observing how the local children interacted with it. According to Mitra, the self-organised learning that took place was enough evidence to support his view that teachers are not needed. We are nothing more than an obstacle to the otherwise inexorable learning that would take place in our absence – a message that plays very nicely into the hands of many EdTech companies, don’t you think?

And how did we all react to this highly controversial claim? We gave the man a standing ovation.

How did it come to this? Why did we – in an attempt not to be teacher centred – allow our classrooms to become materials and text book centred? We outsource our job to videos and audio recordings of dull dialogues.

As teachers, it is our job to inspire – to stimulate and provoke; to fascinate, to engage and to awaken; to build community. And this doesn’t come by fading into the classroom wall. If we want to get our students talking and doing stuff, we first have to talk with them. To do so means finding, embracing and developing our own storytelling voices – learning to talk and learning to listen.

It takes work. It takes reflection. It takes years. But no one ever said it would be easy. Teaching English is reassuringly difficult. Or at least it should be.

About the LessonStream Story Course

LessonStream is a community of teachers, united by our passion for story and storytelling, in and out of the classroom. Members get access to the following:

- The online LessonStream Story Course

- The LessonStream lesson plan library

- The Fishbowl (our online forum)